Over the next several weeks I will post mini articles dealing with types of knives. It is my belief that knowledge is power so the more you know about something the less likely you are to get ripped off.

Fire

Final week

Using knives

"Always cut away from yourself" is the basic adage to keep in mind while using a knife. By extension, assume that the knife is going to slip, and look where the blade would go. In Boy Scout parlance, an area within the radius of the arm and blade length combined is called the "blood circle". When checking the blood circle it is best to hold the knife by the blade, otherwise you defeat the purpose.

Knives offered to another person should always be offered handle first.

A sharp knife is often claimed to be a safer knife. Dull knives supposedly lead to excessive use of force to cut materials, increasing the chance that the blade may slip and the force will be transferred to an unintended destination such as the user or another person or object. Also, a dull or damaged knife will inflict a worse wound than a relatively 'clean' cut from a sharp knife. Conversely it can be argued that what is dangerous is not knowing how sharp a knife is and thus how much force to use.

A knife should be kept clean, dry and sharp. Steel blades rust easily, but oiling will prevent pitting due to oxidation and tarnish. Most knives are not intended as pry bars or screwdrivers. Either use is likely to break off the tip of the blade, or to bend or break the knife beyond repair. Most high-quality knives are also tempered very hard, so that they will retain an edge longer. However, this also makes them brittle.

Sharpening

Knives are sharpened by grinding against a hard surface, typically stone. The smaller the angle between the blade and stone, the sharper the knife will be, but the faster it will dull. A guide is very helpful. Very sharp knives sharpen at 12-15 degrees. Typical knives sharpen at 22 degrees. Knives that chop may sharpen at 25 degrees. In general, the harder the material to be cut the higher the angle of the edge. The composition of the stone affects the sharpness of the blade (finer grain produces sharper blades), as does the composition of the blade (some metals take/keep an edge better than others).

Examples of sharpening tools are the clamp-style systems, which use a clamp with several holes with pre-defined angles. The stone is mounted on a rod and is pulled through these holes, so that the angle remains consistent. Another variant is the crock stick setup, where two sticks are put into a plastic or wooden base to form a V shape. When you pull a knife up the V, the angle is held for you, as long as you hold the blade perpendicular to the base.

Remove a wire edge (burr) if one forms during sharpening. Use a slighly steeper angle with very light pressure to do so. If not removed, it will break off in use, and the knife will instantly become dull. An alternate method of removing a wire edge is stroking from side to side on a very fine stone, using light strokes. This will flip the burr back and forth as it is ground off.

To feel for a wire edge, move your thumb lightly across the edge. It should come off with no resistance. If you feel a little bit of pull at the edge or the nail is sightly abraded, you may have a wire burr.

Honing stones (also called whetstones) come with coarse and fine grits and can be hard or soft describing whether the grit comes free. Arkansas is a traditional source for honing stones, which are traditionally (though a poor practice) used with water or honing oil. India is another traditional source for stones.

Ceramic hones are also common, especially for fine grit size.

Water stones (both artificial and natural) come in very fine grits. They are stored in water, and develop a layer of slurry which dulls the edge if you hone the blade as if honing into the stone. Generally, these are more costly than oilstones. Oil is not to be used on these.

Oil is sometimes used to lift the metal dust, called swarf, off the stone. This is generally bad to do during polishing. There are better ways than oil to clean a hone. Coated hones, which have an abrasive, sometimes diamonds, on a base of plastic or metal are another kind of hone. Rather expensive, are sharpening blocks made with corundum.

Stropping a knife is sometimes a finishing step. This is traditionally done with a leather strap impregnated with abrasive compounds, but can be done on paper, cardstock, or even cloth in a pinch. It will not cut the edge significantly, but produces a very sharp edge with very little metal loss. It is useful when a knife is still sharp, but has lost that 'scary sharp' edge from use.

Other times the final step is done with a steel. This fine process can effect alignment of the edge. Realigning the edge goes a long way in keeping the knife sharp, as often times, a rolled edge will make an otherwise sharp knife dull.

Mechanical consideration of rolled edges If a knife is used as a scraper or encounters hard particles in softer materials or is used asymmetrically, there may be a sideways load near the tip. In this case the knife should resist bending or breaking. Making some simplifying assumptions about the forces and the knife edge's ability to resist them may shed some light on ideal sharpening.

Assume the knife is thin and the force is applied at the very edge. Sheets of material are bent by stretching the outside or compressing the inside. Both the area taking the force and the lever arm converting force to torque are proportional to thickness, so the bending resistance is proportional to the square of the thickness. (That explains the strength per weight of aluminum, compared to steel.) If the force is applied at the edge, the bending torque is proportional to the distance from the edge. So, in this case, the ideal cross section is proportional to the square root of the distance from the edge. This is a (microscopic) parabola. This contrasts to the usual practice of trying to sharpen knives to a wedge near the edge. Perhaps this sheds light on the function of razor straps and on the practice of using two angle guides to sharpen a knife.

On the other hand if the type of use cannot be predicted, it may be better to sharpen it to a wedge and let the first use bend the edge to an appropriate curve. A wedge shape has the property called "scale invariance". It has the same relative shape for any depth of cut.

Week #3

Blades

Materials

Blades are usually made of steel(s); though there are a few knives using materials like high tech ceramic and titanium, these are very uncommon. Stainless steels have gained popularity in the latter half of the twentieth century because they are highly resistant to corrosion (though they can rust under extreme conditions). Tests done by Razor Edge Systems, and described in their book "The Razor Edge Book of Sharpening" indicate that stainless steel knives hold an edge better than regular steels. Stainless and semi-stainless steels include D2, S30V, 154CM, ATS-34, and 440C. Chromium is the major alloying element in stainless steels, giving them the 'stainless' quality. Steels having high carbon but low chromium content are prone to rust and pitting if not kept dry. As of 2004 there are a variety of exotic steels and other materials used to form blades. Knife manufacturers such as Spyderco and Benchmade typically use 154CM, VG-10, S30V, and CPM440V (aka S60V), as well as high-speed high-hardness tool steels like D2 and M2. Other manufacturers sometimes use titanium, cobalt, and cobalt containing alloys. All three are more ductile than typical stainless steels, but have quite a vocal support group despite concerns about health effects of cobalt content. The craft of Damascus steel may be lost, but marketers today misuse its name to apply to pattern welding, which creates layered and admired patterns. The cost of the process restricts it to high-end knives. There is typically more demand for exotic alloys in the utility, outdoor, and tactical or combat knife categories than there is in the kitchen knife category. Forschner/Victorinox make decent, inexpensive kitchen knives; high-end manufacturers include Wüsthof, Global, Henckels and Böker (Tree Brand). Some manufacturers, particularly of kitchen knives, make ceramic blades; these are harder and stay sharp longer, but because of their brittleness, chip and break more readily.

About Steel

All knife steel is martensitic, which means that small crystal grains and lattice irregularities, that make it hard, are formed as it cools from austenitic structure while hot to ferritic structure while cold. Knife steel has fairly low nickel content, because nickel tends to keep steel in the austenitic structure, even when cold. Stainless knife steels are high in carbon, but "carbon steel" means there is not also a lot of chromium. Stainless steel is steel with very high (12–18%) chromium

content. It is corrosion resistant (though knife steel is less so than higher nickel stainless steel) because, except in acid, one of the metals or one of the oxides is always stable. Stainless steel usually has particles of chromium (or other alloy metal) carbides. These explain its reputation for long wear (the carbides are harder than the metal) and for being harder to sharpen and not taking as good an edge as rustable, low alloy ("carbon") steel (the ceramic particles themselves cannot be sharpened easily.) The bulk hardness and toughness of stainless steel tend to be lower than those of low alloy steel. Vanadium and molybdenum are important alloy metals because they make the gain size smaller, which improves hardness and toughness. Vanadium, and perhaps molybdenum, also increase corrosion resistance.

Week#2 post

Shapes

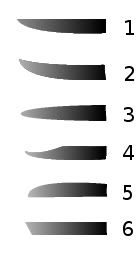

There are a variety of knife blade shapes; some of the most common are listed below.

(1) A normal blade has a curving edge, and flat back. A dull back lets the wielder use fingers to concentrate force; it also makes the knife heavier and stronger for its size. The curve concentrates force on a small point, making cutting easier. Therefore, the knife can chop as

well as pick and slice.

(2) A curved, trailing-point knife has a back edge that curves upward. This lets a lightweight knife have a larger curve on its edge. Such a knife is better for slicing than a normal knife.

(3) A Double edged or spey blade has two edges. The idea is to make a blade that cuts in either direction, with a strong sharp point. This shape is primarily used for fighting knives (daggers, bayonets) because it can cut in both directions and point in line with the handle.

Clip Point blade

(4) A clip point blade is like a normal blade with the tip "clipped" to make the tip thinner and sharper. The back edge of the clip can have a false edge that can be sharpened to make a second edge. The sharp tip makes the blade exceptional as a pick, or for cutting in tight places.

If the false edge is sharpened it increases the knife's effectiveness in piercing. The Bowie has a clipped blade.

(5) A sheepsfoot knife has a straight edge, and a curved dull back. It gives the most control, because the dull back edge is made to be held by fingers. Sheepsfoot knives are good for whittling, including sheep's hooves.

(6) An Americanized tanto style knife is thick towards the point. It is superficially similar to the points on most Japanese long and short swords (katana and wakizashi). The traditional Japanese tanto knife uses the blade geometry of (1). The edge is straight. The point is actually a second edge on the end of the blade, with a total edge angle of 60-80 degrees.

An ulu knife is a sharpened half-circle. This sort of blade is all edge, with no point, and a handle in the middle. It's good for scraping, and sometimes chopping. It is the strongest knife-shape. An example is a head knife, used in leatherworking both to scrape down leather (reducing thickness), and to make precise, rolling cuts to form shapes.

Drop-Point blade

A drop-point blade is very similar to a clip point, but it features the back convexed down, rather than having a clip taken out of it. It handles much like the clip-point.

Week #3 post

Types of knives:

Knives can be categorized based on either form or function.FormKnives exist in several styles:

Fixed blade knives- A fixed blade is a knife in which the blade does not fold and extends most of the way into the handle. This type of knife is typically stronger and larger than a folding knife. Activities that require a strong blade, such as hunting or fighting, typically rely on a fixed blade. Some famous fixed blade designs include the Ka-bar and Bowie knives.

Folding knives- A folding knife is one that has a pivot between handle and blade, allowing the blade to fold into the handle. Most folding knives are small working blades, pocket knives are usually folding knives. Some folding knives have a locking mechanism:

• The most traditional and commonplace lock is the slip-joint. This isn't really a lock at all, and is found most commonly on traditional pocket knives. It consists of a backspring that wedges itself into a notch on the tang on the back of the blade.

• The lockback is the simplest true locking knife. It is found on most traditional locking knives. It is like a slip-joint, but the lock consists of a latch rather than a backspring. To disengage, one presses the latch on the spine of the knife down, releasing the tang.

• The linerlock is the most common today on knives, especially so-called "tactical" folders. Its main advantage is that it allows one to disengage the lock with one hand. It consists of a liner bent so that when the blade opens, the liner presses against the rear of the tang, preventing it from swinging back. To disengage, you press the liner to the side of the knife from where it is attached to the inside of the scales.

• The framelock is a variant of the linerlock, however, instead of using the liner, the frame functions as an actual spring. It is usually much more secure than a liner lock.

• There are many other modern locks with various degrees of effectiveness. Most of these are particular to single brands, most notably Benchmade's AXIS™ lock and SpyderCo's Compression™ lock. Many folding knives (particularly locking models) have a small knob, or thumb-screw that allows the user to open the knife quickly with one hand. Dorsal vs. Ansall In the middle ages, a dorsal meant a knife with a 'back', or a one-sided knife. An ansall was a two-sided knife, with a blade on both sides. These terms have since fallen out of use.

Function

Knife In general, knives are either working (everyday-use blades), or fighting knives. Some knives, such as the Scottish Dirk and Japanese Tanto function in both roles. Many knives are specific to a particular activity or occupation:

• A bread knife is a special knife with a longer, serrated blade especially designed for easily cutting all types of bread. The blade is straight with a blunt end. The serrations (teeth) allow it to cut bread using less vertical force, so keeping the bread from being compressed. They also leave fewer crumbs than most other knives.

• A hunting knife is normally used to dress large game. It is often a normal, mild curve or a curved and clipped blade.

• A scalpel is a medical knife, used to perform surgery. It is one of the sharpest knives available.

• A stockman's knife is a very versatile folding knife with three blades: a clip, a spey and a normal. It is one of the most popular folding knives ever made.

• A dive or diver's knife is adapted for underwater use. Dacor dive knives have tough thermal plastic handles, durable sheaths, and a convenient push-button release, for example.

• Utility, or multi-tool knives may contain several blades, as well as other tools such as pliers. Examples include Leatherman, SOG, Gerber, Wenger and Victorinox (The "Swiss Army knife") tools.

• An electrician's knife is specially insulated to decrease the chance of shock.

• A kukri is a Nepalese fighting and utility knife with a deep forward curve.

Machete blade

• A machete is a long wide blade, used to chop through brush. This tool (larger than most knives, smaller than a sword) depends more on weight than a razor edge for its cutting power.

• A parang, bolo or golok is a knife very similar to a machete but heavier and with a blade designed to move the center of gravity further from the hand for increased chopping power in woodier vegetation.

• A survival knife is a sturdy knife, sometimes with a hollow handle filled with equipment. In the best hollow-handled knives, both blade and handle are cut from a single piece of steel. The end usually has an O-ring seal to keep water out of the handle. Often a small compass is set in the inside, protected part of the pommel/cap. The pommel may be adapted to pounding or chipping. Recommended equipment for the handle: a compass (usually in the pommel). Monofilament line (for snares, fishing), 12 feet of black nylon thread and two needles, a couple of plastic ties, two barbed and one unbarbed fishhook (unbarbed doubles as a suture needle), butterfly bandages, halizone tablets, waterproof matches.

• Special purpose blades may not be made of metal. Plastic, wood and ceramic knives exist. In most applications, these relatively fragile knives are used to avoid easy detection.

• Custom-made knives called microtomes are used to cut specimens for microscopy. The sharpest knives ever constructed are probably the ultramicrotomes with diamond edges used to slice samples for electron microscopes.

• A boning knife is used for deboning meat, poultry, and fish.

• A palette knife is used for spreading icing (frosting). Some palette knives have a serrated edge on one side. (in the U.S. this knife is refered to as a frosting spatula)

For whittling (artistic wood carving) a blade as short as 25mm (1 inch) is common.Serrations on a blade "saw" through the item being cut and stay sharp for a long time. The points protect the slicing areas from nicks. A good serration pattern will stay sharp several times as long as a straight edge.The edge is sharpened at different angles for different purposes. 15 to 25 degrees is a good all-around angle. Slicing knives should have sharper angles, down to ten degrees. Chopping knives need blunter angles, out to thirty degrees.